The Silent Killer of Urban Dogs

by Jennifer Wheeler

Last edited on December 17, 2024

More dogs live in cities than ever before, and these urban pups have access to a reciprocal abundance of new canine goods and services. Yet, just beneath the veneer of polished urban style – dog spas, clubs, and luxury gear – lies an alternative picture of life in the city for many dogs: they cannot cope. They cannot cope with the noise, the people, the busy streets, and the other residents, all the things that make a metropolis a metropolis.

When Ovidiu, a Schutzhund dog trainer, moved to New York in 2002 and founded NYC Doggies he was struck by this unsettling reality. Here was a city full of young, otherwise healthy dogs whose parents had the will and the means to properly care for them, yet many of the dogs he met could not relax outside the comfort of their own homes. This story is the same in cities and towns across the country, and it doesn’t stop at discomfort and nerves. In the worst cases, anxiety and aggression become so unmanageable that dogs are surrendered – thousands of them – to local shelters.

This tragedy is not a symptom of urban life – cities can be a wonderful place to raise a dog. The close-quarters merely make unwanted behaviors more evident. The problem itself stems from something else entirely, from a deficit in early puppy socialization. Largely on the advice of veterinarians and breeders, countless urban dogs are not introduced to the city, its other residents, and its many sensory experiences until their vaccinations are complete at about 16 weeks old. In other words, they are not properly socialized. The risk of getting sick with infectious diseases like canine parvovirus is deemed too high, even though this position stands in stark contrast to the science-based recommendations of animal behaviorists.

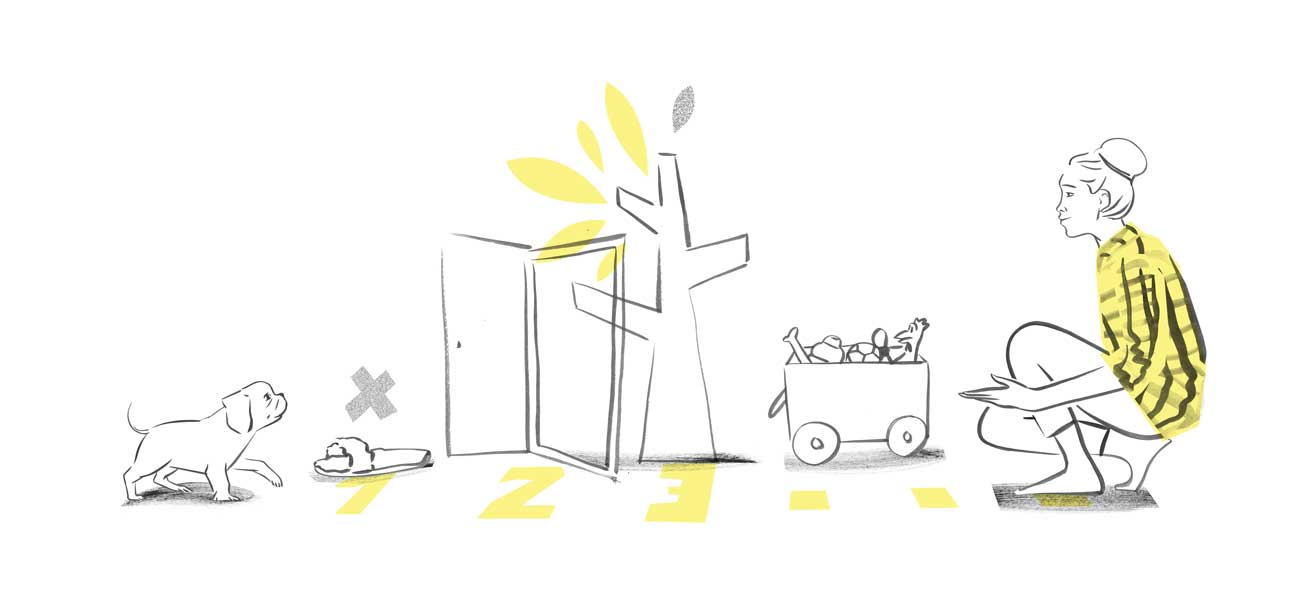

The critical periods of neurological development in puppies are well-researched and conclusive. These are known stages when a puppy’s social experiences of the outside world are inextricably linked to the way her brain is growing. The window for properly socializing a puppy is from 4-12 weeks old, and it is a window. Until a puppy is about three months old, the instinct to be social outweighs fear. New experiences are greeted with curiosity; puppies adapt well to meeting people, other animals, places, sights, and sounds; and, they have the ability to bounce back or overcome any initial doubts about an experience. When the socialized puppy is a bit older, the prior experiences have laid a strong social foundation, and she is much less likely to develop fear, avoidance, or aggression. If the socialization period is missed problems often appear, and when that happens the behaviors can be minimized with a lot of work, but rarely fully extinguished.

The number one killer of dogs under the age of three years is euthanasia due to behavioral problems that develop when dogs are not socialized at a young age.

In 2008, it looked like the debate between medical professionals and canine behaviorists might finally be resolved. The American Veterinary Society of Animal Behavior (an organization that aligns itself with both medical veterinarians and behavioral science) published a position paper that landed firmly on the side of early puppy socialization. Research showed what behaviorists have suspected for decades, that infectious diseases aren’t a leading cause of death in puppies. The number one killer of dogs under the age of three years is euthanasia due to behavioral problems that develop when dogs are not socialized at a young age. This is an astounding finding. As a society, our fear-based instinct to protect puppies from disease has literally sentenced thousands of dogs to their deaths.

This isn’t the only example of how fears about immediate health concerns have led to cultural norms in canine care that are, on balance, not actually in the best interests of our dogs. Over the last two decades we have seen how parents feed, dress, groom, and exercise dogs, with an aversion to immediate risk, which often overrides consideration of long-term benefits. For example, a varied diet that includes some fresh bones, meat, fruits, and vegetables is ideal for canine health. Nonetheless, concerns like choking and the presence of harmful bacteria are enough to deter most dog owners from adding fresh food to their dog’s kibble even though these risks can be mitigated with a little care and consideration.

Two things set early puppy socialization apart from other conversations in canine care: the stakes are extremely high, and there is a scientific consensus about the best course of action. In further support of the AVSAB position, the American Veterinary Medical Association published a review of literature in 2015 that unequivocally advocates for early puppy socialization. The available scholarship, again and again, reaches the conclusion that puppies need to be socialized – ideally every single day – before they are fully vaccinated.

The failure of experts who provide frontline advice to strongly advocate for early puppy socialization is disastrous. We hear again and again from new puppy owners that their breeder or veterinarian instructed them to keep their puppy isolated until fully vaccinated, or at most, to join a puppy class. Let it be noted – a weekly puppy class is not enough, not even close. We meet urban puppies who have never set foot outside of their apartments, greeted the postman, or played with another dog. The subsequent problems develop quickly, and by the time these puppies are 4-5 months old odd behaviors are developing; traffic and bicycles spark anxiety, the puppy isn’t playing well with other dogs, and signs of aggression are starting to appear. These are parents who have followed the advice of the experts in their community, and whose dogs will suffer the consequences for the rest of their lives. Unlike dogs who live in the countryside, these dogs will never be able to avoid the disruptive stimuli that define the urban environment they inhabit.

The problem could merely be a failure to keep up with the science, but we suspect it runs a bit deeper, that a simple proscription feels safer than trusting the ability of dog parents to socialize their puppies safely. It is true that the task is not an easy one; nothing about raising a dog is easy. Safely exposing a vulnerable puppy to the world and all of its beautiful and ugly layers takes planning, effort, and judgment, but isn’t that what parenting is all about?

Life is full of possibilities that walk the line between risk and danger, of choices that help us grow but require good judgment to stay safe. Just as we let our kids climb trees despite the risk of falling, young puppies must be socialized to the urban world despite the risk of illness. Their lives, quite literally, depend on it.

About the author

Jennifer is a writer and graduate of NYU School of Law. Jennifer researches and writes original, science-based articles for the NYC Doggies blog, and her writing on other topics can be found in the Huffington Post. Jennifer and Ovidiu have co-authored the upcoming book, WHOLE DOG PARENTING: EVERYTHING YOU NEED TO RAISE AND TRAIN AN URBAN PUP

love this, valuable info. will be recommending this to my clients to read. Dakine Shiba Inus Oregon and CA. Also was an Expert Speaker for The Ultimate Dog Summit 2019.